Climate change impacts on migrating eels

QUESTION

Freshwater eel fisheries are reliant on the successful migration of adult and juvenile Shortfinned and Longfinned Eels to and from the Coral sea, respectively. How might the changing marine climate, and marine heatwaves, impact of migration, survival, biology and behaviour of eels?

ANSWER 1

Written response:

This is a complex question, but the life cycle of Australian freshwater eels is equally complex, and many factors can influence migration, survival, biology, and behaviour of eels. Australian Shortfinned and Longfinned Eels are thought to spawn/hatch in the Coral Sea region, likely between New Caledonia and the Solomon Islands, although the exact locations remain uncertain. Eels begin life in the ocean as leptocephali (eel larvae), which spend extended periods at sea before metamorphosing into glass eels and recruiting to coastal and freshwater systems. Leptocephali are thought to semi-passively drift in ocean currents (such as the South Equatorial Current and East Australian Current) during their development. Ocean circulation therefore plays a central role during this phase, as currents determine transport pathways, arrival locations, and the timing of recruitment. Changes in ocean circulation associated with climate change, including for example the strengthening and southward extension of the East Australian Current (as highlighted by Dr Arani Chandrapavan in another question) may alter these pathways and increase variability in recruitment of glass eels.

Marine and terrestrial heatwaves may further affect early life stages by modifying coastal and river water conditions, which then influence food availability from the early recruiting stage (glass eel) through to later life stages. With potential consequences for survival and behaviour, although direct evidence for Australian eels remains limited.

Eels then spend many years growing in freshwater as elvers, yellow eels, and silver eels before undertaking a single, long return migration to the ocean to spawn. While recent research has highlited that changes at sea may influence adult migration routes and travel times, some of the most significant and immediate pressures occur in freshwater. Pollution of catchments, habitat loss, diseases/parasites, and migration barriers reduce growth, body condition and survival during the freshwater phase, which can impair swimming performance and overall fitness before ocean migration. These freshwater stressors can carry over into the marine phase and potentially interact with changing ocean conditions. Overall, eel populations are likely to be affected by climate change at sea, and may already be so, but maintaining healthy freshwater habitats remains one of the main factor in supporting successful ocean migration and reproduction. Eel scientists around the pacific use a range of analytical tools, such as stable isotopes, environmental DNA, tagging, morphometric monitoring, traditionnal knowledge…etc, to try to understand the fundamental aspects of eel’s life cycle. And a lot remains un-answered.

Scientists such as Wayne Koster and Alexis Farr may be able to add some information to that question.

Attached are two photos and links to papers that address these issues from a broader perspective, including global threats to freshwater species (including eels) and a representation of the threats that affect eels’ life cycle at different moments.

Nature 2025 (Threats on freshwater species)

Global Ecology and Conservation (Threats on eels’ life cycle)

Supporting gallery:

Answered by:

Alexandre Che-Pelicier

ANSWER 2

Written response:

Knowledge gaps in eel biology

Despite decades of research, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the biology and ecology of anguillid eels worldwide. The complex life cycle of eels (spanning oceanic spawning grounds, larval drift, estuarine recruitment, freshwater growth, and return oceanic migration) presents numerous challenges for research. These knowledge gaps are particularly pronounced for Australian eel species, the short-finned eel (Anguilla australis) and the long-finned eel (Anguilla reinhardtii). Critical aspects of their biology remain poorly understood, including precise spawning locations (presumed to be in the Coral Sea), specific environmental cues triggering migration, optimal thermal ranges during different life stages, and the physiological mechanisms underlying their remarkable oceanic migrations. This limited understanding makes predicting climate change impacts on Australian eels particularly challenging.

Compounding threats to eel populations

Eel populations globally face multiple, well-documented anthropogenic threats that have contributed to dramatic population declines since the 1980s. These include habitat destruction and fragmentation through dam construction and river modification, pollution from agricultural and urban runoff, overfishing of both juvenile and adult life stages, and barriers to migration that prevent eels from completing their life cycles. The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) has been listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, highlighting the severity of these cumulative impacts. Climate change will not occur in isolation but will interact with and exacerbate these existing stressors. For instance, warming waters combined with reduced river flows due to drought will concentrate pollutants, whilst migration barriers will become even more problematic if eels must navigate them during periods of extreme temperatures or altered hydrological conditions. These compounding effects create a particularly precarious situation for eel populations already under significant pressure.

Climate change impacts on marine species

Climate change is fundamentally altering marine environments through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Rising ocean temperatures are the most direct impact, with warming occurring both as gradual increases in mean temperatures and as acute marine heatwave events that are becoming more frequent and intense. Ocean acidification, resulting from increased atmospheric CO₂ absorption, is reducing seawater pH with consequences for marine organism physiology and behaviour. Temperature changes affect fish at multiple levels: “temperature is the master abiotic factor that controls and limits fish development and physiology at all stages” (Islam et al., 2021). Beyond direct physiological effects, climate change triggers trophic cascades throughout marine ecosystems. Warming waters reduce primary productivity as “primary production of eukaryotic phytoplankton appears to be reduced by warm water conditions” (Miller et al., 2021), affecting food web dynamics from the base upwards. For species dependent on specific thermal windows or particular prey assemblages, these changes can be catastrophic. Coral bleaching events, increasingly common in warming oceans, fundamentally alter reef community structure, reducing habitat complexity and prey availability for reef-associated species. These cascading effects ripple through entire ecosystems, affecting species even if they can physiologically tolerate the direct temperature changes.

Evidence of climate change impacts on eels

Whilst the available research focuses primarily on European (Anguilla anguilla) and other Northern Hemisphere eel species, the findings provide important insights that are likely applicable to Australian eels given their shared phylogeny, similar catadromous life history, and comparable migration strategies.

- Temperature effects on migration and survival: Research demonstrates that temperature fundamentally influences eel migration timing and success. Mestav et al. (2024) found that “the preferred migration temperature of silver eel ranges from 10°C to 20°C”, and that “migration occurs when temperatures decline”. Their analysis of 54 years of catch data revealed that “elevated summer temperatures in Turkish waters pose a threat to eel habitat, and our findings indicate that rising surface temperatures significantly reduced eel habitat quality”. Critically, they noted that “the silver eel stage may be more susceptible during migration, which coincides with periods of extreme climatic fluctuations, particularly in summer and autumn, when nocturnal temperatures exceed 20°C”. This temperature sensitivity is particularly concerning given that eels migrate “predominantly within a narrow period (less than a month in a year) in groups, [which] might expose the species to rapid climate change”. During oceanic migration, eels encounter substantial temperature variation. Burgerhout et al. (2019) documented that “European eels showed a temperature range between 8 and 13 °C, with a daily average of 10.1 °C” during the first 1,300 km of migration, whilst Japanese eels experienced “a much wider temperature range…namely between 4 and 10 °C during the day and 15–24 °C during the night”. Eels perform “notable diel vertical migrations (DVMs)” which expose them to daily temperature fluctuations that could become more extreme under climate change scenarios.

- Physiological stress responses: Islam et al. (2021) synthesised evidence showing that extreme temperature events trigger cascading physiological responses: “Temperature stress induces reallocation of metabolic energy required for growth and reproduction, massively impacting aquaculture aims. The relocated energy is used to restore physiological homeostasis”. This energy reallocation means that “growth, reproduction and immune performance are decreased” when fish face thermal stress. The review documented that “temperatures beyond the preferred thermal window increase disease susceptibility in fish”, creating a double threat of physiological stress and increased pathogen vulnerability.

- Sensory and behavioural impacts: Perhaps most alarmingly, Borges et al. (2019) demonstrated experimentally that ocean warming and acidification directly impair glass eel migration behaviour. Their study found that “while OW decreased survival and increased migratory activity, OA appears to hinder migratory response, reducing the preference for riverine cues”. They concluded that “future conditions could potentially favour an early settlement of glass eels, reducing the proportion of fully migratory individuals”. The mechanism appears to involve sensory impairment, as “high pCO₂ and associated pH reduction is thought to impair sensorial information perception, constraining behavioural responses”. This is critical because successful eel recruitment “is highly dependent on their ability to orient and swim towards riverine cues (e.g. temperature, salinity gradients and inland water odours)”.

- Larval stage vulnerabilities: Miller et al. (2021) identified potential impacts on the larval stage of eels, noting that leptocephali “appear to feed on marine snow particles as their primary food source”, and “because primary production of eukaryotic phytoplankton appears to be reduced by warm water conditions, there may be reductions of marine snow production when ocean surface layer temperatures become warmer as a result of global warming”. This could result in “reductions of marine snow abundances…which could also reduce larval survival and cause slower growth rates”.

- Reproductive and maturation impacts: Environmental conditions influence eel silvering and reproductive maturation. Burgerhout et al. (2019) noted that “it has been proposed that decreasing photoperiod and/or a decrease in temperature accelerates the last stages of the silvering process”. Changes in rainfall patterns could also be significant, as “seasonal patterns of rainy seasons may influence the timing of downstream migration and spawning of anguillid eels” (Miller et al., 2021). Mestav et al. (2024) highlighted the vulnerability of migration-dependent species: “if the silver eel starts migrating in response to rainfall, extreme temperatures will halt migration due to unfavourable physical conditions, and confine eels in isolated water bodies, where a hypertrophic crisis will ultimately lead to their death or increase their vulnerability to predation and capture”.

- Habitat suitability projections: Modelling studies project severe habitat reductions. Mestav et al. (2024) found that “by 2050, habitat suitability decreased from 72% at present to 34% for the optimistic climate-change scenario and 27.3% for the pessimistic climate-change scenario. By 2070, habitat suitability decreased to 28.2% for the optimistic climate-change scenario and 14.5% for the pessimistic climate-change scenario”. These projections underscore the magnitude of potential impacts on eel populations.

Conclusion

Returning to the central question: How might the changing marine climate, and marine heatwaves, impact migration, survival, biology and behaviour of eels?

The evidence indicates that climate change poses multifaceted and severe threats to eel populations across all life stages. Rising ocean temperatures and marine heatwaves will likely reduce survival during both the larval oceanic phase and adult spawning migrations, disrupt the critical timing of silver eel downstream migration, impair physiological performance through metabolic stress, and compromise immune function, making eels more susceptible to disease. Ocean acidification threatens to impair the sensory capabilities essential for glass eel recruitment, potentially reducing the proportion of eels that successfully locate and colonise freshwater habitats. Changes in primary productivity will likely reduce food availability for leptocephali, decreasing larval survival and growth rates. Altered rainfall patterns may disrupt the environmental cues that trigger silvering and migration, potentially trapping eels in unsuitable habitats. For shortfinned and longfinned eels migrating to and from the Coral Sea, these impacts (combined with existing anthropogenic pressures) present a critical threat to population sustainability that demands immediate, comprehensive conservation action across their entire migratory range.

Image

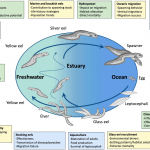

The attached life cycle diagram illustrates why climate change poses such a multifaceted threat to eel populations. Eels transition through multiple distinct habitats. The knowledge gaps surrounding the life cycle (Stuart et al., 2024) emphasise how limited our understanding remains, particularly regarding climate change effects. This is especially relevant for Australian eels migrating to and from the Coral Sea, where existing knowledge gaps compound our uncertainty about climate change impacts.

Original figure caption: Life cycle of anguillid eels, highlighting movements between ocean, estuarine, and freshwater habitats. The life cycle diagram is surrounded by the knowledge gaps identified by Righton et al. (2021), and boxes are positioned near the relevant stage for life-stage-specific questions. Box colour is based on the key themes of the recognised knowledge gaps (adapted from Stuart et al., 2024).

References

- Borges, F. O., Santos, C. P., Sampaio, E., Figueiredo, C., Paula, J. R., Antunes, C., Rosa, R., & Grilo, T. F. (2019). Ocean warming and acidification may challenge the riverward migration of glass eels. Biology Letters, 15(1), 20180627. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0627

- Burgerhout, E., Lokman, P. M., van den Thillart, G. E. E. J. M., & Dirks, R. P. (2019). The time-keeping hormone melatonin: A possible key cue for puberty in freshwater eels (Anguilla spp.). Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 29(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-018-9540-3

- Islam, M. J., Kunzmann, A., & Slater, M. J. (2022). Responses of aquaculture fish to climate change-induced extreme temperatures: A review. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 53(2), 314–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12853

- Mestav, B., Özdilek, Ş. Y., Acar, Z., Gökkaya, K., & Partal, N. (2024). Climate change effects on abundance and distribution of the European eel in Türkiye. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 31(6), e12732. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12732

- Miller, M. J., Wouthuyzen, S., Aoyama, J., Sugeha, H. Y., Watanabe, S., Kuroki, M., Syahailatua, A., Suharti, S., Hagihara, S., Tantu, F. Y., Trianto, Otake, T., & Tsukamoto, K. (2021). Will the high biodiversity of eels in the Coral Triangle be affected by climate change? IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 789, 012011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/789/1/012011

- Righton, D., Westerberg, H., Feunteun, E., Okland, F., Gargan, P., Amilhat, E., Metcalfe, J., Lobon-Cervia, J., Sjöberg, N., Simon, J., Acou, A., Vedor, M., Walker, A., Trancart, T., Bramick, U., Aarestrup, K., Svendsen, J. C., Vowles, A., Azat, C., … Amilhat, E. (2021). Important questions to progress science and sustainable management of anguillid eels. Fish and Fisheries, 22(4), 762–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12549

- Stuart, R. E., Stockwell, J. D., & Marsden, J. E. (2024). Anguillids: widely studied yet poorly understood—a literature review of the current state of Anguilla eel research. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 34, 1637–1664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-024-09892-w