Turning Fish Farms into Climate Allies: Iron and Mussels Lead the Way

- Adaptation story

A global adaptation story (with focus on Asia and the Baltic Sea)

Across the world’s coastlines, scientists and farmers are exploring a surprising new role for aquaculture: a climate solution. Long seen as a sector facing environmental challenges, fish and shellfish farms may instead become critical tools for capturing carbon and buffering ecosystems against climate stress.

At the University of Connecticut, Assistant Professor Mojtaba Fakhraee and his team are pioneering a technique that uses iron enrichment on fish farms. Fish farms generate large amounts of waste, uneaten feed and faeces, that fuel microbes in the sediment below. The result is hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas that harms fish, reduces yields, and damages surrounding ecosystems. But there’s a twist: when iron is added, it reacts with hydrogen sulfide to form iron sulfide, a stable mineral that locks carbon into the seabed while also increasing the ocean’s ability to absorb CO₂.

The potential is enormous. Modelling suggests that farms in aquaculture-heavy nations such as China, Indonesia, and India could collectively sequester at least 100 million tons of CO₂ each year. For China, home to both the world’s largest iron industry and vast numbers of fish farms, the opportunity is particularly compelling: “It may seem unlikely, but fish farms are actually good sites for capturing CO₂,” says Fakhraee. Field trials are now being planned, with farmers invited to participate in testing iron enrichment on their sites.

Meanwhile, in the Baltic Sea, researchers are taking a closer look at mussels. Using advanced models, they’ve shown that mussels not only provide food and filter water but also store carbon in their shells – a form of long-term sequestration if harvested and removed. Results indicate that farms in higher-salinity regions of the western Baltic could capture significant amounts of carbon through shell growth, offering a natural buffer against warming seas and shifting salinity patterns.

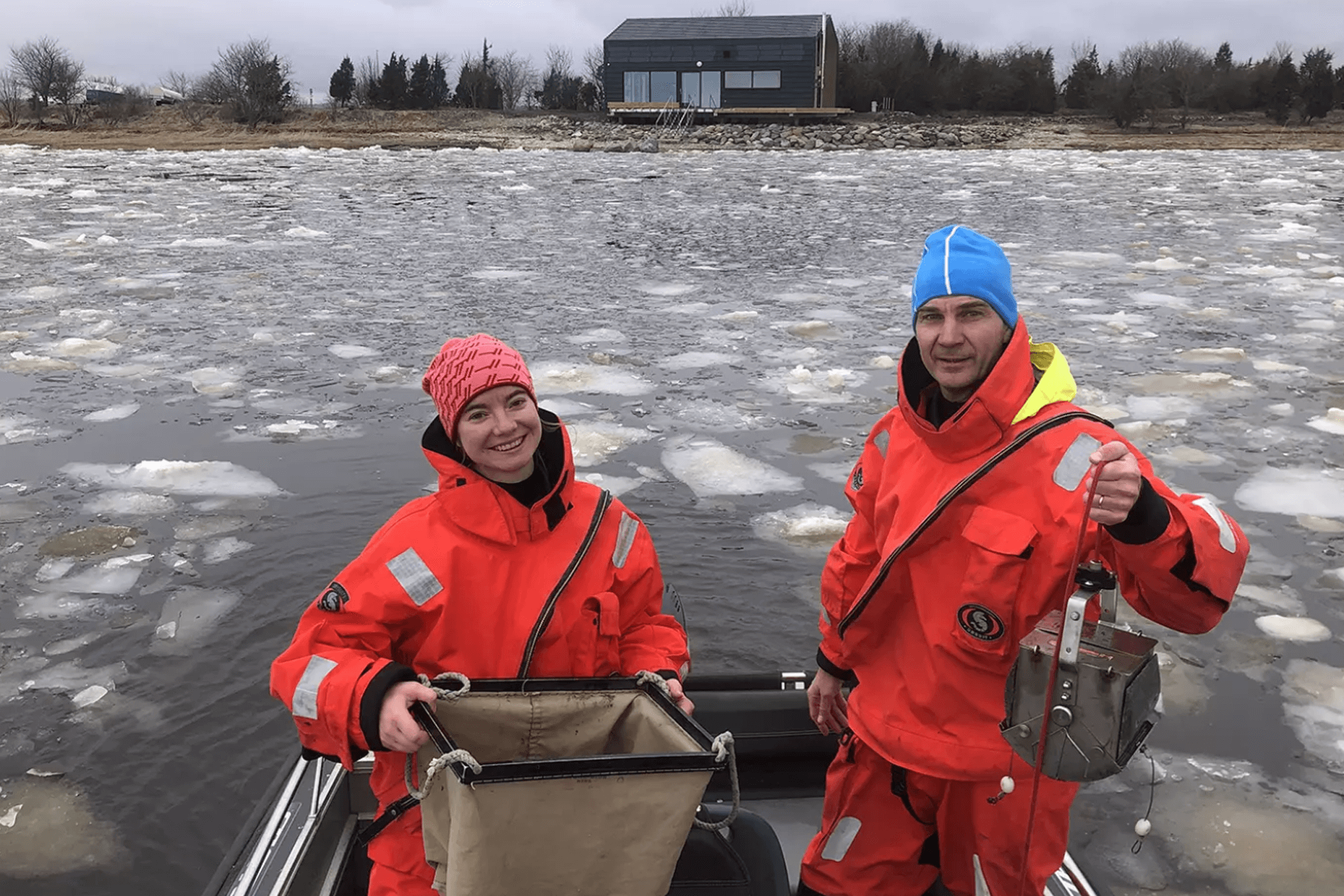

For both fish and mussel farmers, the work represents more than just science. It offers practical co-benefits: reducing toxic hydrogen sulfide, improving farm productivity, and opening the door to new markets built around climate-smart seafood. Farmers in Indonesia have already expressed interest, and a community of practice in Estonia is engaging growers directly to test and refine mussel-based carbon models.

The tools are simple. Iron enrichment requires no complex engineering, and mussel models are being translated into easy-to-use decision tools for farmers and policymakers alike. As Fakhraee notes, “Farmers have been facing issues with hydrogen sulfide for a long time. To know there’s a way to address this problem while also sequestering carbon is a way for them to become engaged.”

Still, uncertainties remain. The scale and permanence of carbon capture, the role of local environmental conditions, and the long-term impacts on ecosystems are all under study. Yet the direction is clear: aquaculture – whether through fish farms harnessing iron chemistry or mussel beds growing natural carbon vaults – could be reimagined as a frontline adaptation strategy.

This story is not just about farming food – it’s about farming solutions. By rethinking the role of aquaculture, researchers and farmers are showing how an industry often criticised for its footprint might instead help write a new chapter in climate resilience.